Battle of Fort Driant – World War II’s Strangest Engagement?

The Battle of Fort Driant was a World War II-era engagement fought between the US Third Army and Germany’s 1st Army from September 27 to October 13, 1944. The fighting itself coincided with the Battle of Metz and the larger Lorraine and Siegfried Line campaigns, taking place in German-occupied France. It’s since been called the strangest battle of the entire conflict.

Fort Driant

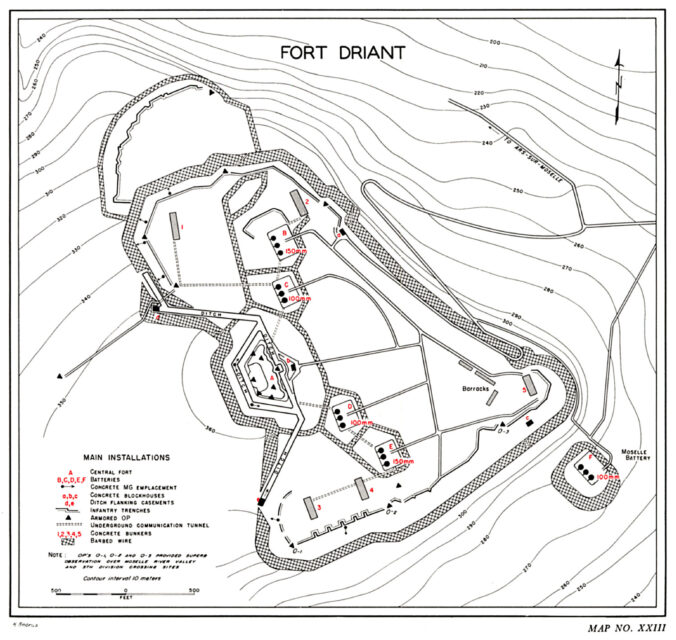

Five miles southwest of Metz and west of the Moselle sat Fort Driant. The fortified installation was constructed in 1902 by the Germans, and was under French control when it was renamed after famed World War I veteran Col. Émile Driant in 1919.

The fortification was constructed of steel-reinforced concrete, with a moat and barbed wire around its perimeter. When the Battle of Fort Driant occurred, it was equipped with four gun batteries – two housing 100 mm guns and the others featuring 150 mm howitzers.

Order of battle

The Metz was integral to Germany’s defensive strategy, in which Fort Driant played a key role. As the US Third Army attempted to take the region, they quickly realized they couldn’t overtake the enemy, falling into a stalemate.

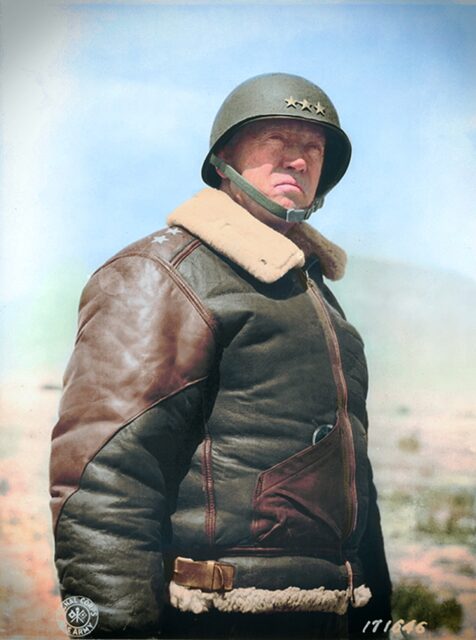

When they attempted to attack the Germans, the Third suffered heavy casualties, and it became exceedingly clear that, if they wanted to take the region, capturing Fort Driant needed to be a priority. Gen. George Patton believed the fortification to be an easy target and tasked the 5th Infantry Division with taking it.

The Third Army was under Patton’s command, while the 5th’s XX Corps was led by Maj. Gen. Walton H. Walker. Fort Driant was defended by the German 1st Army, commanded by Gen. Otto von Knobelsdorff. Gen. Heinrich Kittel was in command of the Metz garrison.

The Battle of Fort Driant commences

The Battle of Fort Driant began at 2:15 PM on September 27, 1944. American-flown Republic P-47 Thunderbolts with the XIX Tactical Air Command made up the first element, dropping 1,000-pound bombs and napalm. The bombing missions stopped once the infantry forces closed in.

This was followed by Companies E and B of the 11th Infantry Regiment and Company C of the 818th Tank Destroyer Battalion attacking from the ground. The initial assault failed, with the advancing troops cut down and the tank destroyers useless against the German defenses.

The Americans attacked a second time on September 29. This included using explosive-filled pipes and bulldozers to fill the trench line around the fort. Despite both proving ineffective, Gen. Stafford LeRoy Irwin still ordered the attack to go ahead as planned.

Once again, the Germans easily held off the Americans. With the help of tanks, a portion of the advancing infantry got through the initial defenses on the southwestern corner. Reaching the barracks, hand-to-hand combat erupted. At the other side of the fort, E Company came under heavy fire and had to dig in for four days outside of the barbed wire.

The American forces become desperate

Becoming more desperate, the Americans attempted to destroy some of the defenses with a self-propelled gun. However, despite being fired from only 30 yards away, it did next to no damage.

The infantrymen fell under heavier fire, including bombardments from other forts and nearby forests. They did, however, gain back their momentum when, like the climactic finale of The Dirty Dozen (1967), a private from B Company removed the ventilator shaft covers atop one of the barracks and threw bangalore torpedoes down them, forcing the enemy troops within to evacuate. The Americans entered shortly after and made the barrack’s the company’s command post.

Initially kept in reserve, G Company, 11th Infantry Regiment was sent in and, like much of the assault, failed to achieve their objective. Despite rising casualties, Patton wouldn’t allow the attack to fail, regardless of if it took every member of XX Corps.

By the start of the second day, both B and E companies had suffered casualties amounting to 50 percent of their original strength. The only objectives reached by that point had been negligible.

The Germans used tunnels to their advantage

The following days saw more attacks, which, again, proved unsuccessful. With an October 5 report from the commander of G Company detailing the position of the assault, Irwin decided more troops were needed, including the 1st Battalion, 10th Infantry Regiment; the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment; and the whole of the 7th Combat Engineer Battalion. It was decided that, with their arrival, the American attacks would resume on October 7.

As the battle progressed, it was discovered the Germans were using tunnels. The Americans began to use those they captured and later considered digging their own. The use of these underground passageways led to the engagement being nicknamed the war’s “strangest battle.”

While they were an effective way of fighting, however, they weren’t always useful. On the morning of October 8, the Americans came up against a large iron door blocking a tunnel. Once through, they could’ve gone further into the fort, attacking the Germans from above- and below-ground. Using a 60-pound beehive charge, they unsuccessfully attempted to blow a hole through the door – only a small gap was created, while a large amount of carbide fumes filled the barracks.

On October 9, Patton held a meeting with Irwin, Walker and Gen. Alan Warnock, sending Gen. Hobart Raymond Gay to represent him. While Warnock suggested digging tunnels and attacking the fort from underground, Gay declined.

American withdrawal

It was believed the men participating in the fighting were becoming “battle fatigued.” It was also clear that engagements in other areas of the Metz were proving much more successful. Gay, with Patton’s agreement, therefore ordered the abandonment of the offensive.

Some back and forth continued until October 13, when all remaining troops were evacuated. As the Americans withdrew, they destroyed the tanks they couldn’t get out and any fortification the Germans could still use, and engineers used 6,000 pounds of explosives to destroy bunkers, shelters and tunnel entrances around the barracks. The barracks, too, were destroyed.

Despite this, it was an evident loss for the United States and a success for German forces.

Aftermath of the Battle of Fort Driant

The blame for the American failure fell upon Irwin. He became a scapegoat, seen as “moving too slow” and “removing the drive” from their advance.

Gen. Omar Bradley, Patton’s immediate superior, recalled telling the general, “For God’s sake, George, lay off […] I promise you’ll get your chance. When we get going again you can far more easily pinch out Metz and take it from behind. Why bloody your nose in this pecking campaign?” Patton responded, “We’re using Metz to blood the new divisions,” in reference to the fact that the majority of his men hadn’t yet experienced combat, given how new they were.

The American forces suffered 798 casualties during the Battle of Fort Driant, including 64 dead, 547 wounded and 187 missing or captured. German losses are unknown. At the conclusion of the engagement, the Americans stood exactly where they had at the start of the campaign.